insight

The Pain in Spain Falls Mainly on the…

April 18, 2012

Spain has come under pressure due to investor concerns about its worsening fiscal profile and struggling banking system. While the country is pursuing a program of fiscal consolidation, it will likely struggle to reignite economic growth and is expected fall into recession during 2012. As a result of twin funding pressures facing both the sovereign and the banking system, we believe Spain will need to turn to the European Union and the European Central Bank for support.

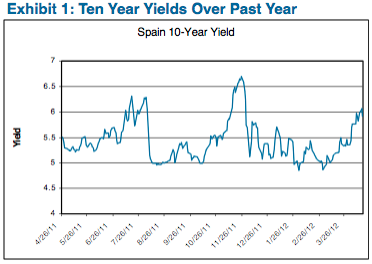

Spain is in the headlines again due to rising capital markets concerns about the country’s fiscal sustainability and the soundness of its banking system. Spanish sovereign ten year bond yields, which had fallen as low 4.85% in February following the completion of emergency liquidity operations by the European Central Bank, have since risen above 6.00% (Exhibit 1). This raises the risk that Spain’s economic problems will be compounded by unsustainably high funding costs, or even potentially a sovereign investors’ buyers strike.

In this “white paper,” we contemplate Spain’s fiscal profile, its banking system and the support mechanisms available to address a funding shortfall in the event Spain loses access to the capital markets. We will conclude with a credit view on the impact on corporate bond markets should Spain be forced to turn to the European Union (EU), the European Central Bank (ECB), or the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for further support.

Sizing the Problem

Risking a much overused cliché, Spain really is “too big to fail” within the European context. With a GDP of €1.07 trillion, Spain is the Eurozone’s fourth largest economy representing 11% of consolidated €9.4 trillion GDP (Greece, by contrast, accounted for 3%).

The inherent imbalances in the Euro system (common monetary policy/divergent fiscal policies) resulted in a real estate bubble in Spain over the past decade and a material increase in leverage at the government level, in the private sector and by the households. As a result, Spain finds itself with unsustainable (and growing) government debt levels, a banking sector that is struggling to de-lever in the face of a burst real estate bubble and an economy that is expected to slip again into recession in 2012.

Spain’s Fiscal Profile

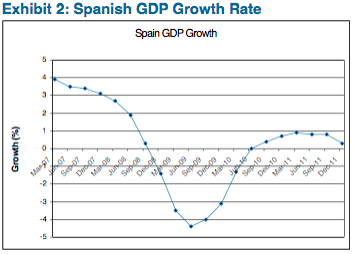

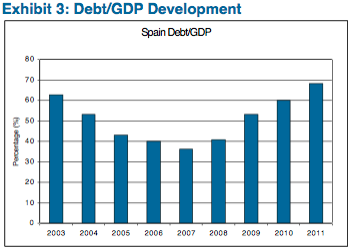

The economic recession that followed the global financial crisis in 2008 accelerated the fiscal imbalances within Spain. A persistent structural budget deficit was aggravated by the recession (Exhibit 2), resulting in a rapid growth of Spain’s debt/GDP measure (Exhibit 3).

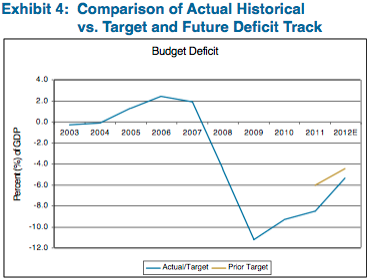

While successive Spanish governments have committed to reducing the structural budget deficit through austerity measures, the slowing economy has frustrated these efforts. As a result, the budget deficit which stood at -9.3% in fiscal year 2010 missed its fiscal year 2011 target of -6.0% by a material margin, coming in at -8.5%. The newly elected government reignited fears about fiscal sustainability in February 2012 when it announced Spain would miss its fiscal year 2012 deficit target of -4.4%. And investors are generally skeptical about the revised target of -5.3%, which appears politically expedient, but economically difficult to achieve (Exhibit 4).

Impediments to Growth

While Spain’s current debt/GDP level actually compares favorably to most of its Eurozone peers, the country’s lack of economic growth, as well as the potential need to support its banking system (more on this below) are the primary drivers of the capital market concerns that threaten its ability to refinance its substantial external debts. While a resumption of economic growth will be key to ultimately reversing the deterioration in Spain’s fiscal profile, there are a number of factors impeding such growth.

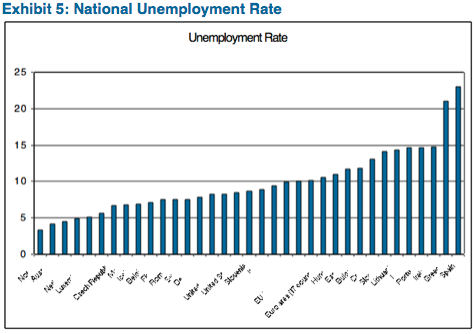

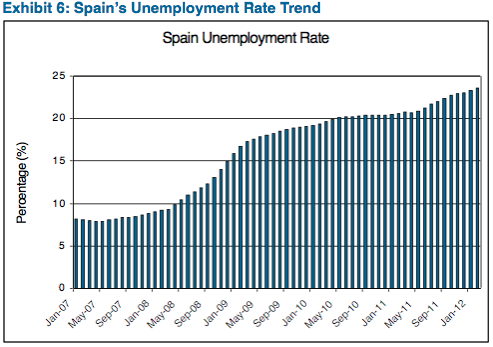

The biggest challenge is Spain’s inflexible labor system, which makes it very difficult for employers to adjust their labor force through lay-offs. The result has been persistently high unemployment, which spiked as a result of the 2009/2010 recession, but made companies reluctant to hire new employees as the country emerged from recession in 2011 (Exhibit 6). Unemployment was also aggravated by the high proportion of the population involved in the Spanish construction industry, which has collapsed following the bursting of the country’s real estate bubble. The imposition of successive austerity programs in an effort to close the budget deficit has further hurt employment in the public sector. As a result, Spain has the highest unemployment rate in the Eurozone at 23%, and unemployment among those under 30 is nearly 45% (Exhibit 5).

The Spanish Banking System

Beyond the impact on employment levels, the collapse of the real estate bubble has left the Spanish banks with an outsized real estate loan book that is suffering from deteriorating asset quality due to the factors discussed above (recession/high unemployment). Just to size the problem, the Spanish banking system had a total loan book of €1.8 trillion (equivalent to 180% of GDP) at year end 2012 and non-performing loans (NPL) were €136 billion (7.6% of loans). Against this, the Spanish banking system has loan loss provisions (LLP) of €108 billion and tangible common equity of €203 billion.

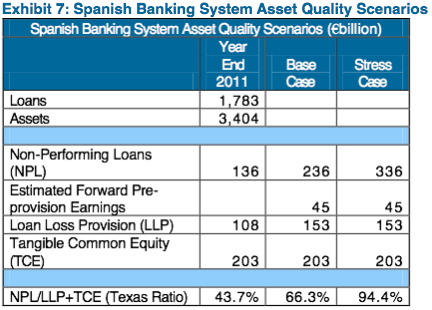

If the economy slips back into recession in 2012, NPLs across all loan classes are likely to grow, but real estate is of particular concern. While the Spanish real estate bubble burst in 2008, real estate prices have fallen far less (down approximately 20-25%) than in other countries with collapsed real estate bubbles (i.e., United States, Ireland). Residential mortgage loans stood at €657 billion (2.8% NPL) while corporate real estate (commercial real estate/real estate development companies) stood at €397 billion (20.1% NPL). Estimates vary, but under the assumption that asset quality continues to worsen in the face of renewed recession and continued decrease in real estate prices, additional provisions required by the banks could range from €100 to €200 billion. With a pre-provision profit generating capacity estimated in the €40-45 billion range, even an increase of provision expense of €100 billion would begin to erode the capital of the banking system. As shown in Exhibit 7, Spanish banks already have a high proportion of NPL to LLP+ Tangible Common Equity (informally known as the Texas Ratio – as it approaches 100% the likelihood of bank failure also approaches 100%).

Regulators have pushed for a consolidation within the banking sector, with stronger banks absorbing weaker banks. But, as we demonstrated with the consolidated bank system ratios above (and the experience of Japan during the ‘90s), such a strategy can only be taken so far before it cripples the entire system. Spanish regulators have attempted to pre-empt this issue by changing bank provisioning standards to require a provision build of approximately €100 billion within the banking system. However, given the limited capacity of the Spanish banks to generate capital organically or through private market capital increases, it is likely that a large portion of this increase will have to come from public sources. To this end, the Spanish government has established the Fund for Orderly Bank Restructuring (FROB) which can provide public capital injections for struggling banks and has injected €14 billion in public capital to date.

However, given the persistent budget deficit and growing debt/GDP ratio, Spain can ill afford to inject a further €50-150 billion in capital. With outstanding sovereign debt of €735 billion and a debt/GDP ratio that officially stood at 68% at year end 2011, every additional €50 billion of capital injected into the bank sector raises the ratio by five percentage points (and this is before contemplating the budget deficit and GDP contraction).

Spain’s Dual Liquidity Crunches (Squeezes/Crises?)

As a result of its fiscal and banking challenges, Spain faces dual liquidity squeezes on its access to sovereign funding in the bond market and bank funding in the deposit and wholesale markets.

Within the sovereign debt markets, this is reflected in Spain’s debt costs, with yields on existing debt rising above a 6% yield, reflecting sovereign investors’ unease over Spain’s fiscal sustainability. Yields substantially above the country’s own GDP growth rate raise the question of long-term sustainability of the country’s debt load and aggravates the growing debt/GDP ratio. At the extreme, the rising yields reflect growing unwillingness of sovereign debt investors to support Spanish debt. With issuance needs of approximately €185 billion for 2012 (including €100 billion of short-term bills that must be refinanced), the potential that investors decline to purchase Spanish sovereign issuance raises the real prospect of a sovereign default.

The Spanish banking system has already effectively lost access to the wholesale funding markets and investors have pulled away from Spanish bank bonds on fears about the system’s solvency in the face of rising credit costs. At the same time, retail and institutional deposits have been migrating from the Spanish banking system and into banking systems viewed as more stable (Germany/Netherlands/France). A funding crisis has been averted only through reliance on the European Central Bank’s (ECB) emergency lending programs. However, ECB liquidity is only a temporary solution, and its requirement for collateral against funding advanced is rapidly encumbering Spanish bank balance sheets (and effectively subordinating unsecured bond holders, thus further reducing the likelihood that they resume funding the banks). Furthermore, while ECB liquidity stems concerns about an immediate bank failure, it does nothing to address market concerns about the solvency of the Spanish banking system.

Crisis Fighting Options for Spain

While Spain would ideally prefer to address its sovereign funding and bank funding/solvency issues internally, it already appears that this option is not available. At a minimum, the need for the banking system to access ECB liquidity is a tacit admission that Spain is unable to provide support. There appear to be two options that Spain and the EU can utilize to tackle the current crisis:

- European Central Bank Liquidity – As noted above, the Spanish banking system is already accessing ECB emergency liquidity through the Longer-term Refinancing Operation (LTRO), through which the ECB provides unlimited three year loans to banks in return for collateral (paradoxically, the LTRO liquidity provided to the banks has largely been reinvested in Spanish sovereign debt, temporarily lowering Spanish sovereign yields, although this effect is temporary). Additionally, the ECB has provided indirect liquidity support to struggling Eurozone sovereigns through its Security Market Purchase (SMP) program which purchases sovereign debt in the secondary market with the goal of reducing yields. While the ECB has theoretically unlimited capacity to provide liquidity at both the banking and sovereign levels, practically these measures amount to a stopgap. Regarding bank funding, we have already noted that the LTRO funding for banks is limited by the stock of eligible collateral, and cannot provide capital infusions to address solvency concerns. And on the sovereign funding level, SMP has been highly controversial in the EU, with some nations (especially Germany) opposing it as a backdoor quantitative easing that could ultimately stoke inflation. Because the SMP is not a formal support program that imposes fiscal conditions on borrowers, but rather an open market program, it is a temporary liquidity stopgap, rather than a formal tool for addressing fiscal imbalances. To this end, the ECB Board has explicitly warned that the SMP should not be viewed as unlimited, and that addressing the fiscal challenges of the Eurozone must be undertaken at the governmental/fiscal level rather than being tackled by the monetary authority (ECB).

- EU Crisis Programs – Since the advent of the Eurozone crisis in mid-2010, the EU has established two separate funds to aid struggling sovereigns as they undertake fiscal consolidation. The European Fiscal Stability Fund (EFSF) was intended as a temporary €440 billion fund. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) was established by treaty in 2011 as a €500 billion permanent replacement to the EFSF. In an attempt to add credibility in the face of multiple sovereign crises during 2011, the EU agreed to accelerate the advent of the ESM to July 2012 (although the ESM has yet to be ratified by all EU members). To date, three countries (Greece, Ireland and Portugal) have entered a fiscal consolidation plan with support from the EFSF/ESM programs (with varying success). The use of EFSF/ESM programs to aid Spain through its sovereign and banking crises has several pros including: (a) flexibility to fund a defined program of fiscal consolidation, and (b) the ability to provide direct recapitalization of the Spanish banking sector, thus taking pressure off the sovereign. However, there are also several hurdles to such an approach. First, it would require an explicit Spanish request for assistance, and any program Spain entered into would require it to surrender a degree of sovereignty to the EU administrators of the program (and the new government has already expressed reservations about encroachment on Spanish sovereignty). More practically, the EFSF/ESM programs are “committed” but unfunded, and would require substantial issuance of bonds jointly and severally guaranteed by all EU members. This raises questions both of the market’s capacity for absorbing such funding needs (above and beyond what has already been committed to Greece/Ireland/Portugal). Furthermore, the creditworthiness of the EFSF/ESM relies entirely on the credit of the underlying members, of which Spain is one of the larger members, raising questions about the creditworthiness of the EU as a whole. Ultimately, the credibility of the EFSF/ESM rests in large part on the willingness and capacity of the EU’s strongest member, Germany, to support weaker EU members. This appears ultimately to be political rather than financial question, and subject to domestic political and economic considerations. We believe Germany will ultimately decide that it is in its own best interest to support its fellow EU members, but this outcome is by no means a certainty.

Conclusion: Expectations and Credit Implications

We believe that Spain likely will need to request formal support from the EU/ECB/IMF sometime during 2012 or 2013 (and potentially much sooner). The likely form of support is via a negotiated program utilizing the EFSF/ESM (rather than continued ad hoc support through the ECB). The most likely driver of the request in the near-term would be a continued rise in sovereign funding costs beyond the point of sustainability. However, even in the event that funding pressures ease, Spain is likely to face increased pressure to enter a formal program, either from the ECB which is unlikely to provide permanent open ended funding for its banking system, or from the EU if it slips behind schedule on its fiscal consolidation program (which we believe is likely).

The resolution of Spain’s fiscal and banking challenges has credit implications for both Spain and the broader EU. Failure to address Spain’s economy (and all of the struggling Euro area’s economies) in an orderly manner would ultimately threaten the existence of single currency, and could result in serious disruption to the European economy and financial system. We believe that the most likely outcome is a collective agreement by EU members to preserve the currency while working through fiscal consolidation of the weaker economies. Ultimately, this likely results in a greater degree of fiscal integration within the EU (a necessity if the single currency is to survive) and we do NOT rule out the possibility of further sovereign restructurings (in the mold of Greece) although that is not our default expectation with Spain (given their relatively stronger fiscal profile). However, the challenge of achieving political consensus among the seventeen Euro currency members and the twenty seven European Union members has already made itself evident in the manner in which the EU has stumbled from crisis to crisis. We expect this approach to continue, and as such, believe that the investment grade corporate bond markets will be subject to recurring episodes of volatility surrounding fiscal/political developments in the Eurozone.

Consequently, we remain very cautious on corporate issuers with direct exposure to the weaker EU sovereigns (Telefonica/Iberdrola) and have also reduced our exposure to all European banks (given the interconnectedness of European bank funding of EU sovereign debt issuance). We are also cognizant of the impact of EU credit volatility on the U.S. money center bank sector, although fundamentally the U.S. banks have very manageable direct exposures to Europe.

N. Sebastian Bacchus, CFA

Vice President, Corporate Credit

For more information, contact:

Greg Curran, CFA

Vice President, Business Development

greg.curran@aamcompany.com

Disclaimer: Asset Allocation & Management Company, LLC (AAM) is an investment adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission, specializing in fixed-income asset management services for insurance companies. This information was developed using publicly available information, internally developed data and outside sources believed to be reliable. While all reasonable care has been taken to ensure that the facts stated and the opinions given are accurate, complete and reasonable, liability is expressly disclaimed by AAM and any affiliates (collectively known as “AAM”), and their representative officers and employees. This report has been prepared for informational purposes only and does not purport to represent a complete analysis of any security, company or industry discussed. Any opinions and/or recommendations expressed are subject to change without notice and should be considered only as part of a diversified portfolio. A complete list of investment recommendations made during the past year is available upon request. Past performance is not an indication of future returns.

This information is distributed to recipients including AAM, any of which may have acted on the basis of the information, or may have an ownership interest in securities to which the information relates. It may also be distributed to clients of AAM, as well as to other recipients with whom no such client relationship exists. Providing this information does not, in and of itself, constitute a recommendation by AAM, nor does it imply that the purchase or sale of any security is suitable for the recipient. Investing in the bond market is subject to certain risks including market, interest-rate, issuer, credit, inflation, liquidity, valuation, volatility, prepayment and extension. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission.

Disclaimer: Asset Allocation & Management Company, LLC (AAM) is an investment adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission, specializing in fixed-income asset management services for insurance companies. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. This information was developed using publicly available information, internally developed data and outside sources believed to be reliable. While all reasonable care has been taken to ensure that the facts stated and the opinions given are accurate, complete and reasonable, liability is expressly disclaimed by AAM and any affiliates (collectively known as “AAM”), and their representative officers and employees. This report has been prepared for informational purposes only and does not purport to represent a complete analysis of any security, company or industry discussed. Any opinions and/or recommendations expressed are subject to change without notice and should be considered only as part of a diversified portfolio. Any opinions and statements contained herein of financial market trends based on market conditions constitute our judgment. This material may contain projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events, targets or expectations, and is only current as of the date indicated. There is no assurance that such events or targets will be achieved, and may be significantly different than that discussed here. The information presented, including any statements concerning financial market trends, is based on current market conditions, which will fluctuate and may be superseded by subsequent market events or for other reasons. Although the assumptions underlying the forward-looking statements that may be contained herein are believed to be reasonable they can be affected by inaccurate assumptions or by known or unknown risks and uncertainties. AAM assumes no duty to provide updates to any analysis contained herein. A complete list of investment recommendations made during the past year is available upon request. Past performance is not an indication of future returns. This information is distributed to recipients including AAM, any of which may have acted on the basis of the information, or may have an ownership interest in securities to which the information relates. It may also be distributed to clients of AAM, as well as to other recipients with whom no such client relationship exists. Providing this information does not, in and of itself, constitute a recommendation by AAM, nor does it imply that the purchase or sale of any security is suitable for the recipient. Investing in the bond market is subject to certain risks including market, interest-rate, issuer, credit, inflation, liquidity, valuation, volatility, prepayment and extension. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission.