Saudi Arabia has pegged its currency, the Riyal, to the U.S. Dollar at a rate of 3.75 since 1986. Below we highlight the rationale for the peg and the benefits it has provided to the Kingdom over the years. We also explore how weak oil prices, the Covid-19 pandemic and large fiscal deficits are undermining its economic profile. While we believe the probability of a de-peg or devaluation is currently low, we highlight issues that may lead to change in the Riyal-Dollar regime and the consequences it would lead to in the energy sector.

- A change to the Riyal-U.S. Dollar regime is a low-probability high-risk event

- Historically stable peg has provided benefits making future changes difficult and costly

- Shrinking FX reserves contribute to currency risks

- Future issues to monitor include Vision 2030, shrinking economy, change to Iran policy

- If risks materialize there is substantial downside for fixed income energy investments

The reasons for the Riyal – U.S. Dollar peg and historical benefits

In October 1973, in response to apparent US involvement in the Arab-Israeli War, Saudi Arabia led an Arab oil embargo against the US that led to the world’s first global oil shock. Despite the embargo ending after five months, OPEC kept prices elevated, putting significant pressure on the external finances of the US. In response, the Nixon Administration struck a deal with the Saudi government in 1974 whereby the Dollar proceeds of US purchases of Saudi oil would be reinvested by the Saudi government in US Treasuries. The Saudis also agreed to price oil in US Dollars globally. In return, the US provided the Saudis with military aid and equipment. This was the foundation of the petrodollar system which helped the US Dollar regain its global supremacy after the collapse of Bretton Woods and has linked Saudi oil revenues and savings to the US Dollar to this day. (1)

Like today, in the 1970’s the vast majority of the Saudi economy was US dollar based and its savings were being invested in US Treasuries, yet the Riyal was pegged to the International Monetary Fund’s Special drawing rights (SDR). The SDR, an artificial currency instrument at the time was calculated from a weighted basket of major currencies, including the U.S. Dollar, Deutsche Mark, the French Franc, Japanese Yen and British Pound. This currency mismatch and a roaring Saudi economy led to very high inflation, which peaked at 35% in 1975. After the oil crash in the early 1980’s, the Saudi devalued its currency and pegged it to the US Dollar at 3.75 Riyals per Dollar. It has remained pegged at this level for the past 34 years.

The Riyal-Dollar peg has provided monetary stability in that exchange rates have remained stable and inflation has rarely been higher than 5% since the current peg was established in 1986. The peg has also provided some revenue predictability, a desirable characteristic given that its economy is highly dependent on volatile oil prices. Lateral benefits include lower lending rates and credit growth. Furthermore, according to an analysis by Goldman Sachs, the cumulative current account balance since 1998 (i.e., net FX savings of the economy) is as much as $400 billion greater now than it would have been under a floating exchange rate regime. (2)

Confidence Remains in the Riyal – U.S. Dollar regime

A key feature to maintaining a fixed FX regime is confidence that the domestic country (in this case Saudi Arabia) holds adequate FX reserves of the pegged country (in this case U.S. dollar reserves). Taiwan, for example, was largely immune to the Asian crisis of 1997-98 due to its large holdings of foreign exchange reserves. The measure that is commonly used to evaluate this coverage is FX reserves to M1 money supply, or narrow money.

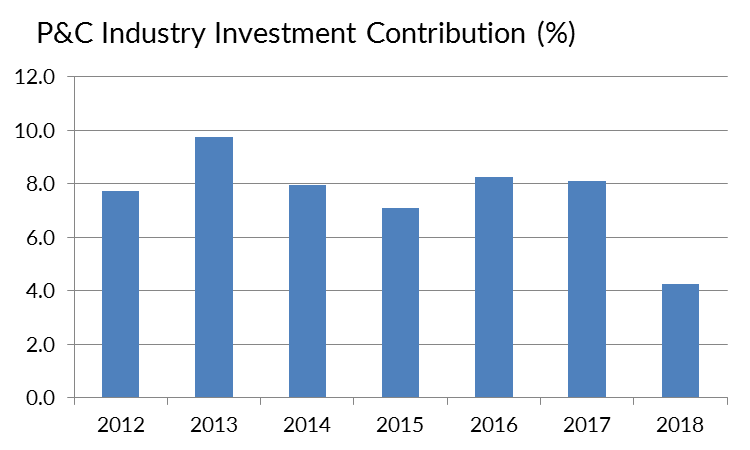

Exhibit 1 shows that while the Saudis still have adequate coverage of narrow money (around 200% of M1), net reserves have declined to $742 billion (including sovereign Private Investment Funds) and they are expected to continue to decline given the expected budget deficits for the next several years.

Exhibit 1: FX Reserve Coverage Deteriorating

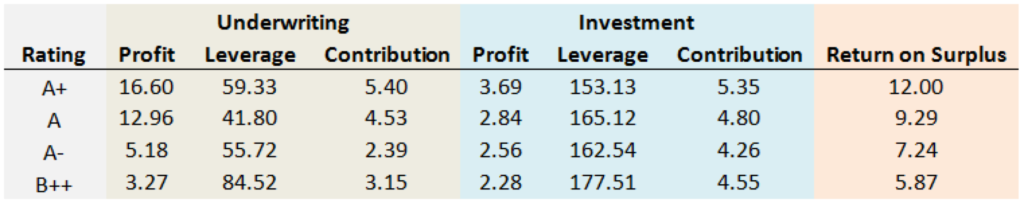

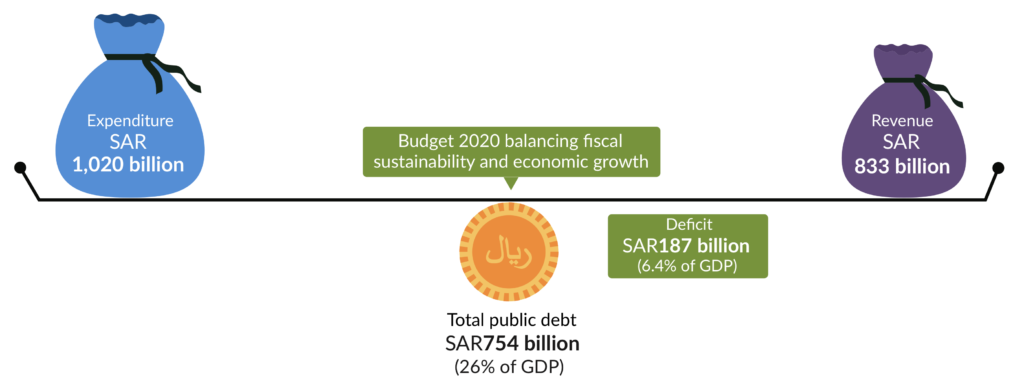

According to the IMF, “the negative affects of the pandemic, significantly lower disposable income for oil exporters after the dramatic fuel price decline, imply a sharp recession in Saudi Arabia of –6.8%.” Additionally, the government agency suggests that Saudi Arabia will be running a budget deficit of 11.4% ($89 billion) and 5.6% ($44 billion) in 2020 and 2021, respectively. This deficit will have to be funded either by further drawing down reserves or issuing additional debt. A draw of the reserves further weakens the coverage of narrow money. Raising debt is the more likely avenue as the government said last month that it planned to raise its debt ceiling from 30% to 50% of gross domestic product as it borrows more to cope with the crises (Exhibit 2). Either approach will likely result in further downgrades of the Kingdom by the rating agencies.

Exhibit 2: Saudi Arabia External Debt as % of GDP

In response to the present economic challenges, fiscal deficits, and funding hurdles, in May 2020 the Saudi Finance Minister announced several fiscal measures to improve government finances by approximately $30 billion. These measures include the discontinuation of a cost-of-living allowance for public employees, a value-added tax that will increase from 5% to 15% as of July 2020 and substantial cuts in spending on key Vision 2030 infrastructure projects. The cost-of-living allowance represented about 10% for earnings of Saudi nationals, and its discontinuation will thus cut real incomes.

Considerable Challenges Likely to Erode Confidence

The Kingdom faces a significant dilemma – it can continue to fund its ambitious Vision 2030 transformational plan with fiscal deficits and maintain support from its young population or delay progress, maintain near term fiscal health yet risk losing the vital support from its growing labor pool. So far, it appears as though it is choosing to plow ahead with the plan and live with meaningful fiscal deficits.

The Kingdom’s estimated $1 trillion Vision 2030 program to diversify the economy and sustain living standards in a less oil dependent world is viewed positively from Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman’s base of support. The Crown Prince promised that Vision 2030 would deliver economic prosperity and millions of new private sector jobs for young Saudis. If these economic benefits appear to grow more elusive, public endorsement for the Vision 2030 agenda may dissolve and threaten the strong backing from the public. However, with Saudi Arabia’s finances increasingly squeezed, funds are being diverted from the Vision 2030 plan to offset the economic slump. In early May, the Saudi’s apparently cut $8 billion from the budget as part of its austerity actions. (3)

In addition to substantial expenditures, we believe the threat of growing deficits is rising due to shrinking revenues. According to the Saudi Arabia Monetary Agency, more than 60% of private sector employment is in the Retail, Transportation and Construction industries, all are focal points of the Vision 2030 plan and all have been hit by the pandemic due to the lockdown. As the Kingdom undergoes a second wave of the virus and limits the number of people allowed to perform the annual pilgrimage, we believe those industries will experience more pain and the budget deficit will grow (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: 2020 Budget Analysis

Of equal concern is the outcome of the U.S. Presidential election in November 2020, the potential changes to Iranian foreign policy and how that may affect oil prices. Many polls currently indicate Senator Joe Biden is leading President Trump by 5%-10% in the upcoming election. Should Senator Biden win the election, there is likely to be important changes to U.S. foreign policy toward Iran. Many of the leading architects of the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action nuclear deal are senior Biden foreign policy advisors and a renegotiation of that agreement could be a key foreign policy priority. It has been reported that one plan being considered by these advisors would allow Iran to export around 700,000 barrels of oil per day. This would negatively affect oil prices and could result in another round of market share fighting between Saudi Arabia, Iran, and other OPEC+ members.

Moreover, Biden has stated to the Council on Foreign Relations that he wants a “reassessment” of U.S. support for Saudi Arabia in the wake of the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, the Saudi-led war in Yemen, and domestic human rights violations. Furthermore, he also stated he would stop arms sales to the kingdom (recall that this was one of the pillars of the original Riyal – US Dollar regime) and treat Riyadh like a “pariah” on the world stage. (4) Taken as a whole, we believe a Biden victory would likely diminish the already deteriorating economic health of Saudi Arabia.

Implications to Saudi Arabia and Energy Markets of a Change to the Riyal – U.S. Dollar Regime

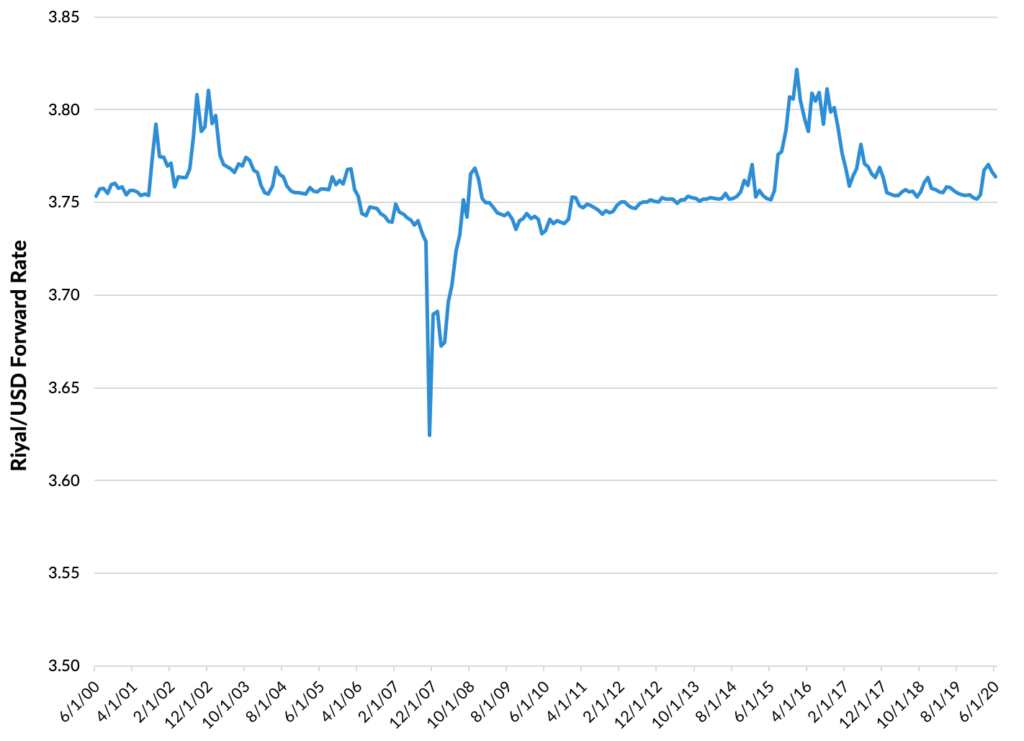

We believe the likelihood is low of a de-pegging or devaluation of the Riyal given the stability the relationship has provided historically, the commitment to the peg from the Saudi Arabia Monetary Agency and the size of a cut necessary to achieve coverage of narrow money in a low oil environment. According to Goldman Sachs, over a three-year horizon, a minimum 50% devaluation would keep reserves above the narrow money level in absolute terms but under a $30 oil environment a devaluation of at least 80% would be required to stabilize the reserves. (5) The foreign exchange market is also discounting the threat of a devaluation over the next 12 months as seen by the stable forward FX rate in Exhibit 4.

Exhibit 4: 12 Month Forward FX Rate Riyal per USD

However, given the risks we have highlighted to the Saudi economy and therefore its Foreign Reserves, we believe the possibility of a devaluation will rise over the next several years particularly if oil prices remain in the $40 range or if few fiscal adjustments are made. Below we highlight consequences of a change.

According the New York Fed, generally speaking there are two implications of a devaluation: 1) it makes the pegged country exports relatively less expensive for foreigners; 2) it makes foreign products relatively more expensive for the pegged country’s consumers, thus discouraging imports. The first point is more critical to oil prices and energy markets. The second point is more critical specifically to Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia’s major export, oil, is dollar based and a devaluation would have little bearing on output levels and exports. However, on the revenue side, a depreciation in the Riyal, would increase oil revenues for Saudi Arabia, as every barrel of oil sold will bring in more Riyals for a given Dollar oil price. We believe a weaker Riyal thus would enable the Saudis to maintain or increase production levels in a market share battle with other oil producers and still address their budget shortfall. Therefore, a de-peg or meaningful devaluation of the Riyal would have negative implications for oil and energy markets. A de-peg or devaluation combined with Iranian exports returning would have significantly negative implications for oil prices and the entire energy sector. This scenario likely would result in downgrades and higher yields for many investment grade energy companies and defaults for weaker positioned companies in the high yield energy sector.

With regards to the second point from the New York Fed, Saudi imports represent a relatively high proportion of domestic consumption. Consequently, a real danger of de-pegging or devaluing the Riyal is higher inflation in Saudi Arabia. This would of course likely be followed by higher interest rates to control that inflation. Additionally, to the extent that devaluation is viewed as a sign of economic weakness, the creditworthiness of the nation may be jeopardized, it would likely dampen investor confidence and hurt the country’s ability to secure foreign investment. (6) This would conflict with the country’s desire to increase foreign direct investment as part of the Vision 2030 plan. Mitigating this concern somewhat, is that the Saudis could reduce the need to implement unpopular fiscal spending policies (like cutting Vision 2030 expenditures) and would boost aggregate demand in the economy to fight unemployment.

Summary

Saudi Arabia is facing significant challenges in the next several years and how it chooses to address them will affect oil prices and investment grade energy companies. Expenditures to develop an economy less dependent on oil combined with shrinking oil revenue is leading to deteriorating financial conditions. A high-impact low-probability event to address shrinking reserves and expanding fiscal deficits is to de-peg or devalue its currency. While market confidence in the peg remains, there are considerable risks on the horizon that we will continue to monitor. If the risks we highlighted materialize, there are downside perils to both oil prices and investment grade energy investments.

- Andrea Wong, “The Untold Story Behind Saudi Arabia’s 41-Year U.S. Debt Secret,” (Bloomberg), May 2016

- Farouk Soussa, “Saudi Riyal Peg Has Served Economy Well, Likelihood of Devaluation is low,” (Goldman Sachs), May 2020

- Paul Cochrane, “Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030: Can Saudi Arabia afford it?,” (Middle East Eye), June 2020

- Candidate Tracker, (Council on Foreign Relations), December 2019

- Farouk Soussa, “Saudi Riyal Peg Has Served Economy Well, Likelihood of Devaluation is low,” (Goldman Sachs), May 2020

- Currency Devaluation and Revaluation, (Federal Reserve Bank of New York), September 2011