In the investment industry, there is a widely-held view that a Core Fixed Income strategy is a commodity. The belief is that there are variations among managers and styles of course, but over time those distinctions will offset, and there will ultimately be an immaterial difference in returns. Further, with yields across the investment grade universe near historic lows, the distribution of returns across managers should be even less substantial on a relative basis.

Removing the noise

The question necessarily becomes, is there evidence to support this belief? Or are there in fact significant differences in returns over longer periods of time? If there are, the costs of assuming homogeneity could be more significant than investors realize. We wanted to explore this concept further, but to do so objectively, it was essential to level the playing field by eliminating as much noise in the data as possible. Return differences between core managers can most often be explained by two factors: managing to either different benchmarks or duration targets, and/or a measurable allocation to “non-core” or below investment grade securities.

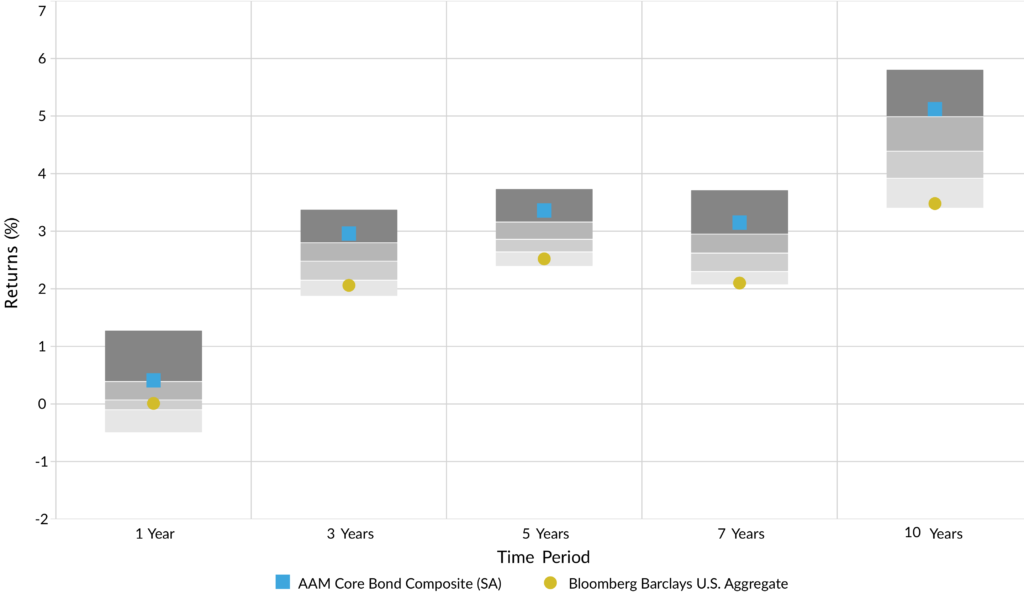

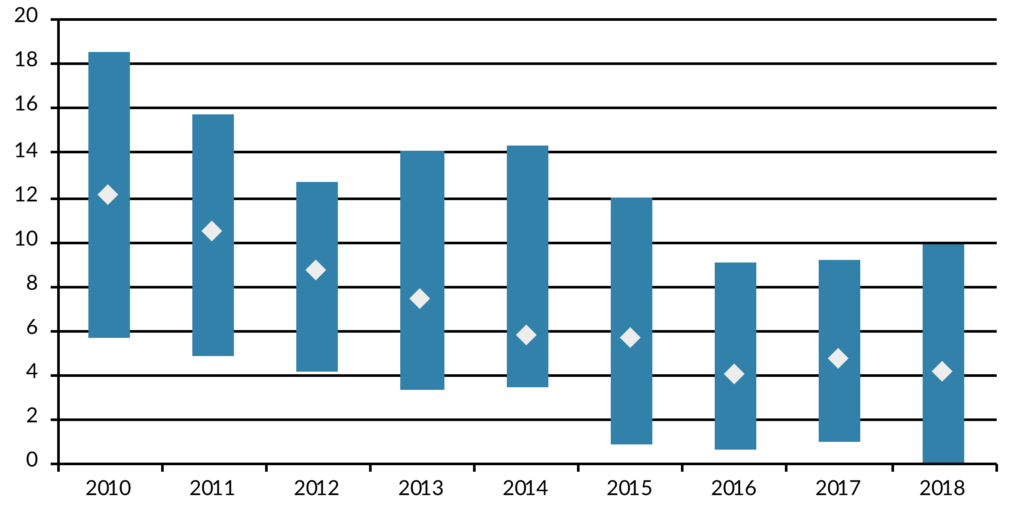

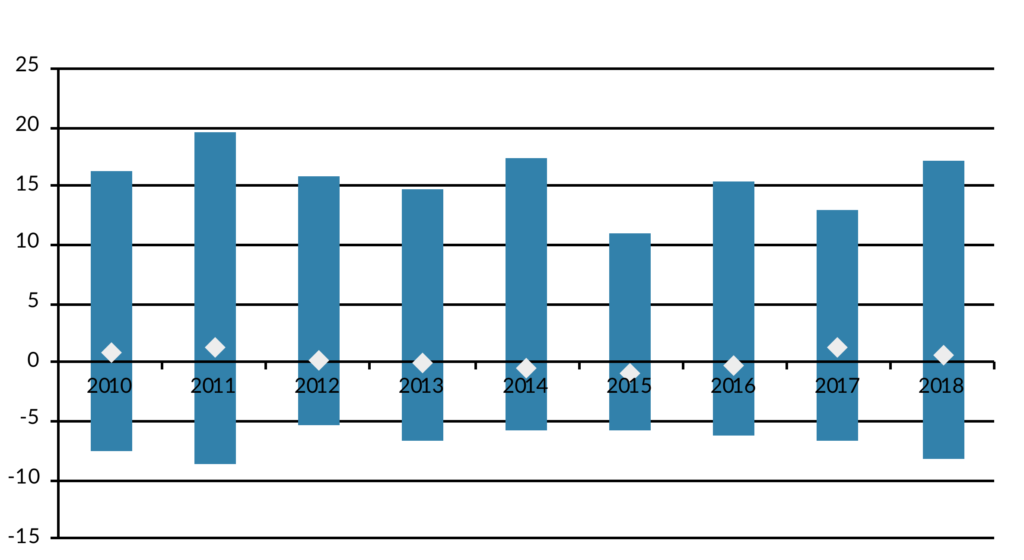

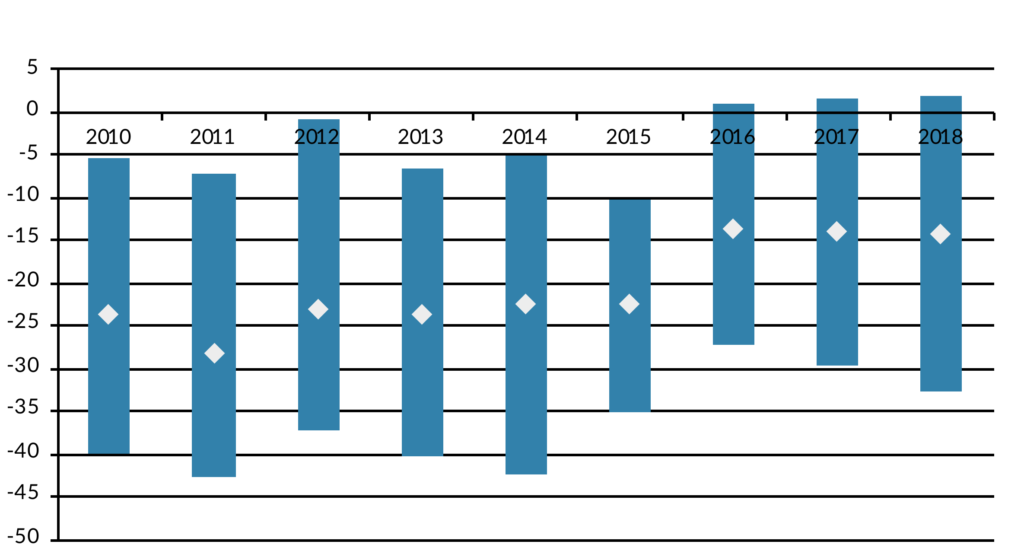

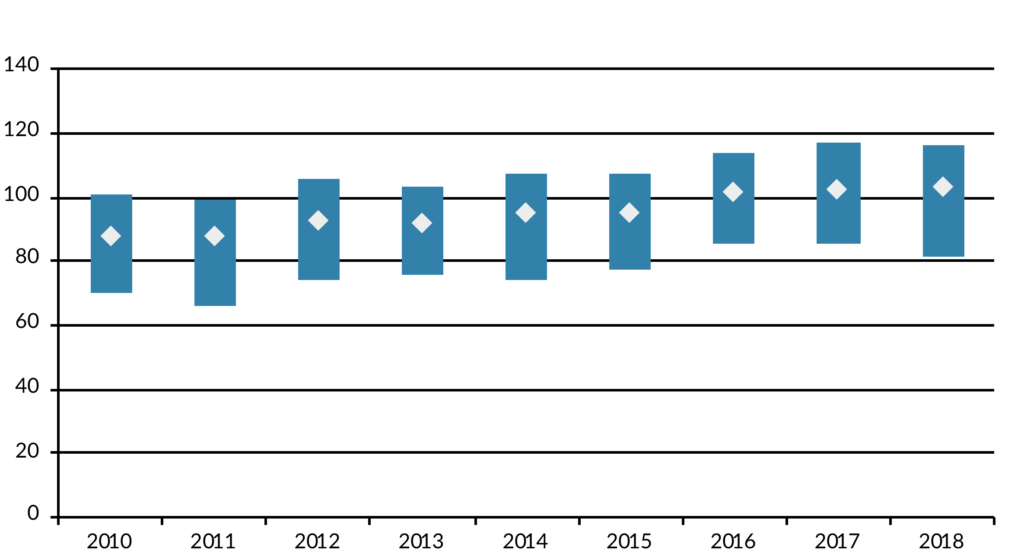

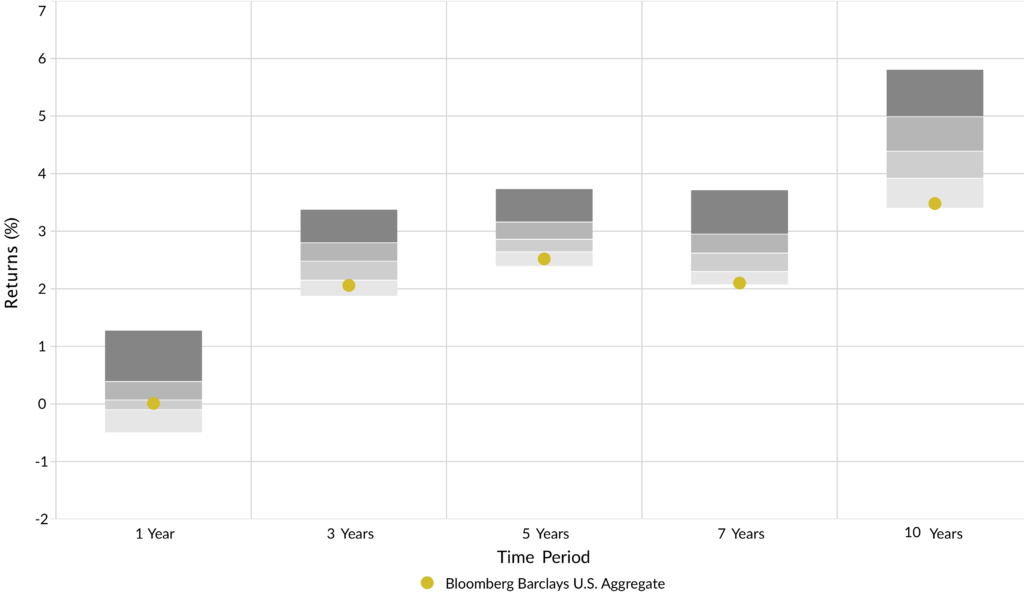

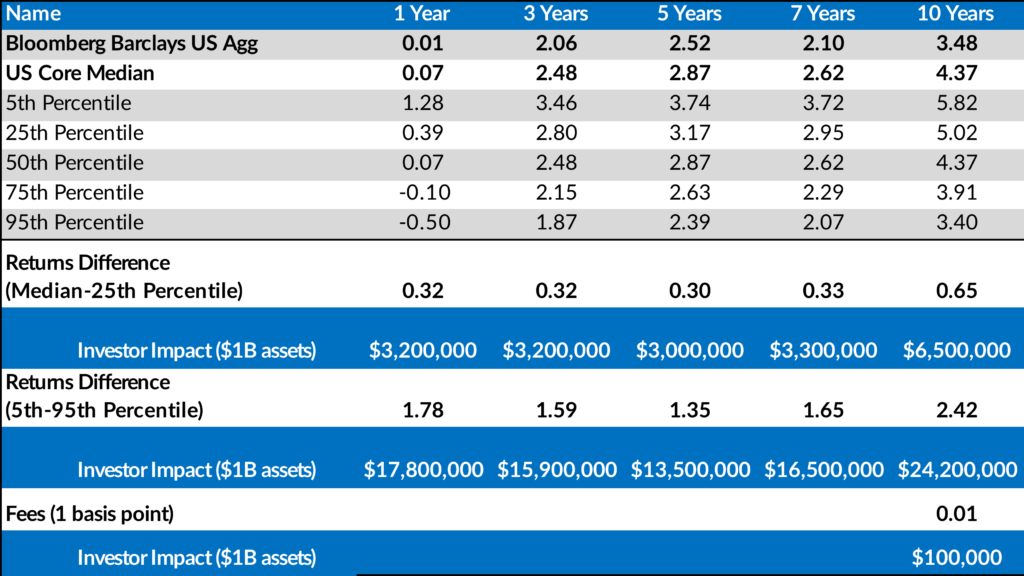

With these factors in mind, we evaluated a universe of institutional core managers with the most comparable objectives and characteristics we could find. The Core managers in this peer group all list the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Index as their primary benchmark, share a common duration range, and have an inconsequential allocation to “non-core” bond sectors such as High Yield, Emerging Markets, or non-US dollar assets. Finally, all return statistics for these managers were viewed gross of fees to further eliminate any nuances caused by variations in expenses. In other words, we constructed the most “commoditized” group of US institutional core managers possible. In Exhibit 1 we show the distribution of historical returns for the US Core peer group over the last 10 years. Even over the longest time interval (10 years) the average annualized return difference between the 5th and 95th percentile manager is substantial at 2.42%. In economic terms, that return differential has an impact on investors of $24.2 million a year for every $1 billion in assets. Even the difference between the median core manager and one that performs in the top quartile is significant at 0.65% on average or $6.5 million each year by the same measure (Exhibit 2).

Institutional investors are rightfully mindful of paying reasonable fees to Core managers. Hiring decisions for a new manager in a competitive process are sometimes made with the difference of basis points in management fees being a critical input to who is selected. Comparatively, every 1 basis point (0.01%) in savings for the same $1 billion in assets costs $100,000 less a year. That’s a prudent input for an investor to analyze, but can pale in comparison to the costs of a manager that doesn’t produce competitive returns.

Exhibit 1: US Core Fixed Income Distribution of Returns

Exhibit 2: US Core Fixed Income Distribution of Returns – Investor Impact

Exploring the differences

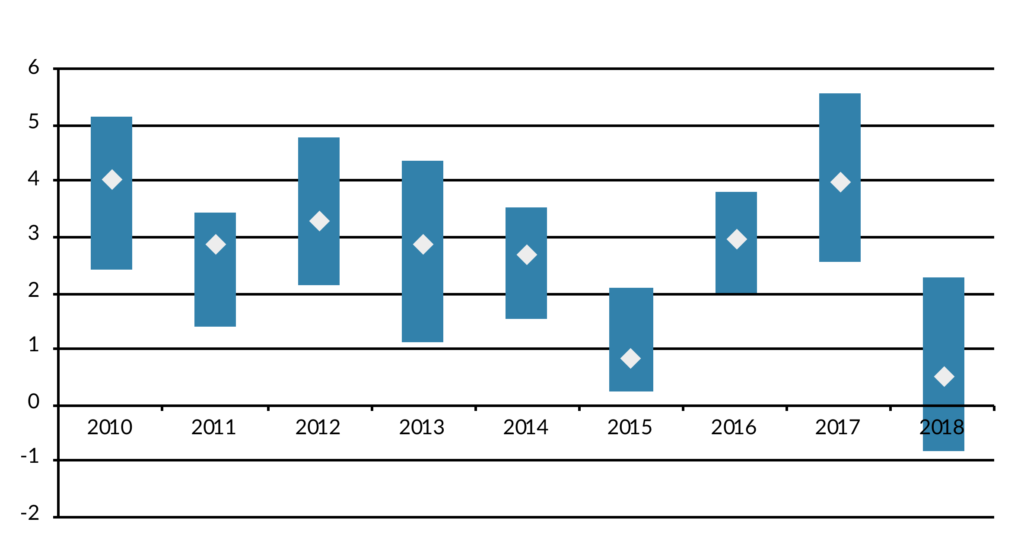

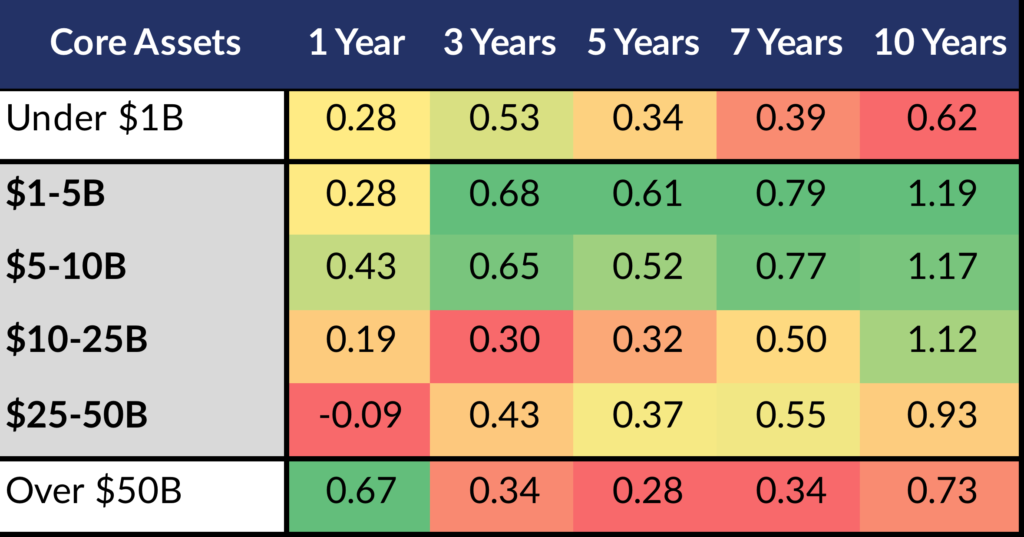

So if performance does in fact affect returns for investors, what is driving the differences in a low interest environment? When you dissect the core universe by asset size, there is a consistent pattern of excess returns relative the benchmark as measured by Alpha. Exhibit 3 shows a heat map of the average Alpha generated by core managers within each core assets category. The colors move gradually from dark green representing the highest (and therefore best) Alpha to dark red representing the lowest. Noticeably, the mid-size managers with core assets ranging form $1 billion-$50 billion exhibited consistently superior performance over all periods longer than 1 year, while both the largest and smallest managers were consistently the worst performers over longer periods of time.

Exhibit 3: Alpha

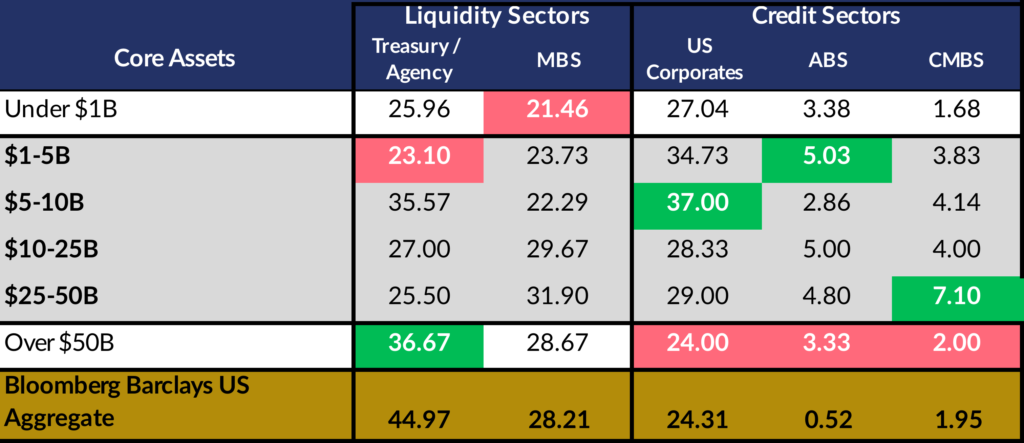

One way to analyze this underperformance is to explore the average sector allocation along the same size segments we examined above. In Exhibit 4, the table highlights that larger managers had hefty allocations to liquidity sectors such as US Treasury and Agencies and the lowest allocation to credit related sectors that traditionally offer more yield. Green indicates the highest average allocation in the peer group while red indicates the lowest. We can see that the $50 billion and over category had the lowest allocation to credit sectors and the most benchmark-like sector allocations overall. This helps explain why the largest managers appear to have the most difficulty delivering excess returns as their positioning closely aligns them with the benchmark itself. For the smaller managers who underperformed, sector allocation alone does not offer a clear explanation. However, a likely consideration is they lack the resources or scale to allow full access to bond dealer offerings.

Exhibit 4: Investment Grade Sector Allocation

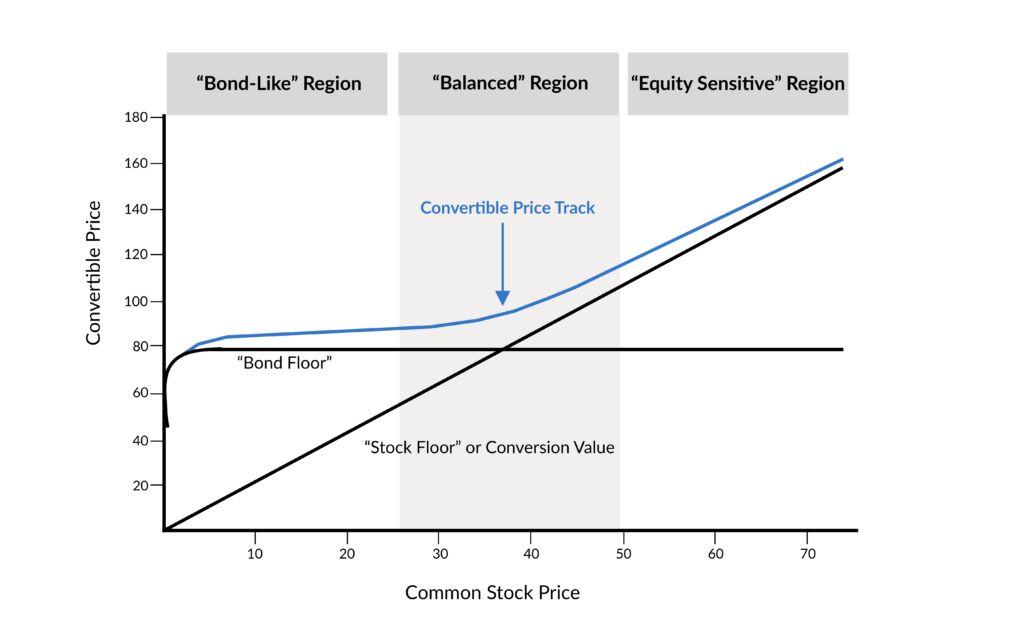

Identification versus execution

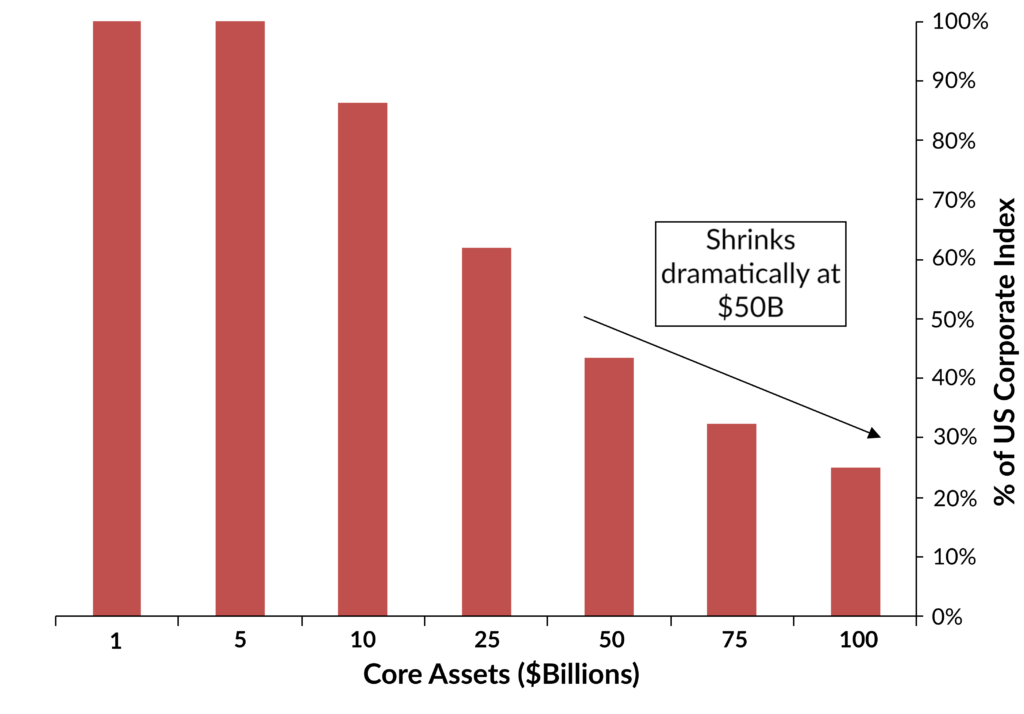

It stands to reason that the largest managers have more difficulty allocating to credit sectors simply because these sectors make up a much smaller portion of the investment grade universe. And even if you successfully allocate to these sectors, it is even more challenging to accumulate an overweight position in a particular bond that offers good value. To illustrate this point, Exhibit 5 shows the percentage of the US Investment Grade issuers that are large enough for a manager to accumulate a 0.5% position, again segmented by manager asset size. We highlight 0.5% because it represents the largest corporate holding in the Bloomberg Barclays US Aggregate Index. So by default, a 0.5% represents an overweight position relative to the benchmark for any other holding. In other words, if a manager buys a 0.5% position in a bond and it performs well, your portfolio outperforms the benchmark because you own a larger position.

As you can see in the chart below, the corporate issuers a manager can overweight shrinks dramatically for managers with assets above $50 billion. Less than half of the index is eligible at $50 billion and only 25% of issuers are large enough at $100 billion. This indicates that implementing trade ideas becomes increasingly difficult for strategies above $50 billion given the limited supply of corporate issuers that are large enough to buy a meaningful position. These managers have the ability to purchase the issues of course, but it is much more difficult to accumulate more than the benchmark’s position size, making it challenging to outperform.

Exhibit 5: Percent of Corporate Market Managers can Overweight (0.5% position)

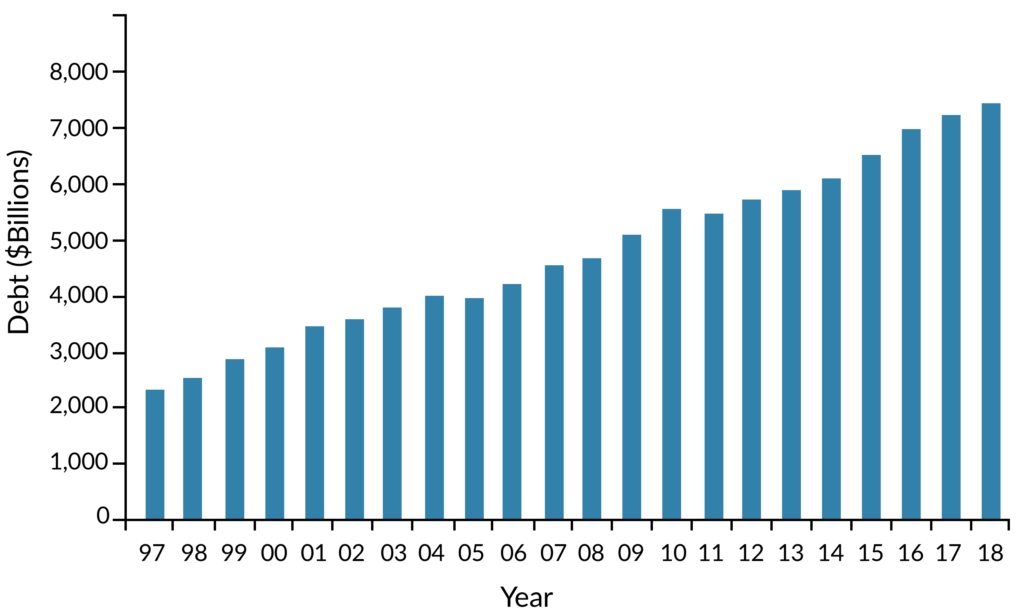

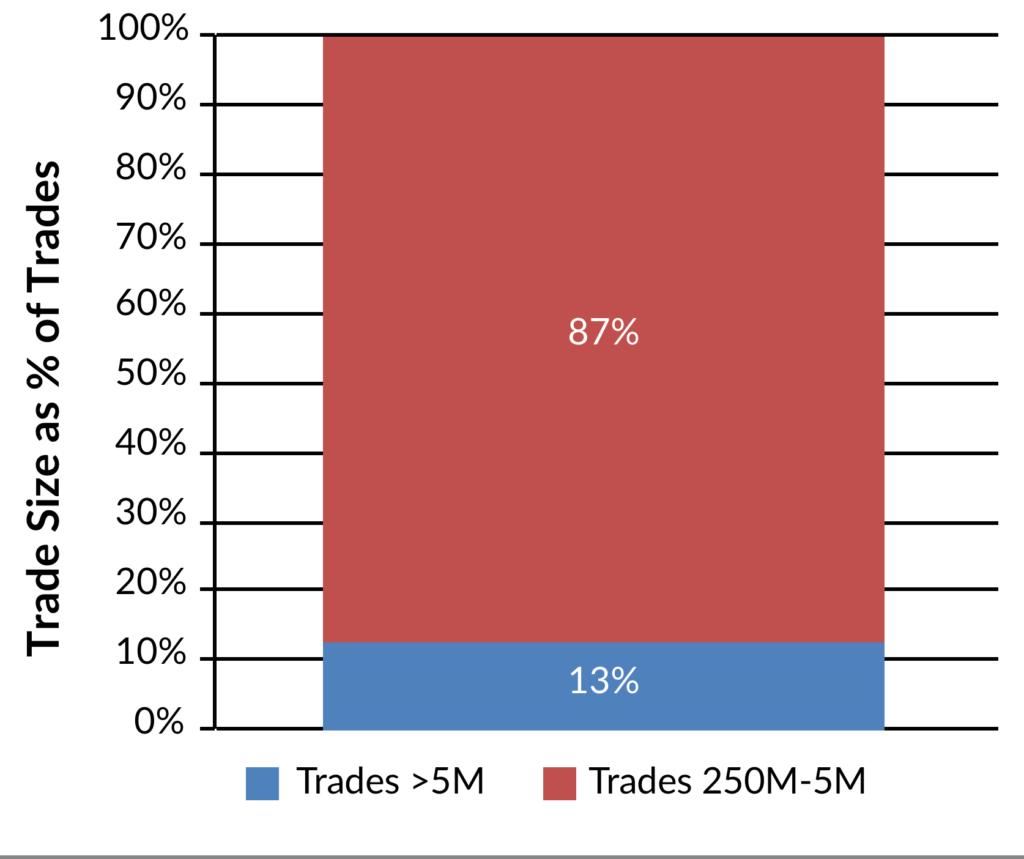

While this example addresses issues related to purchasing bonds, it also pertains to the potential difficulties these same firms encounter when trying to sell large positions whenever credit or valuation concerns arise. The ability to trade large bond positions has declined significantly as bond dealer corporate inventories continue to fall as a regulatory consequence of the financial crisis. At the same time, investment grade debt outstanding has ballooned to all time highs. Put together, because dealers have less capital to make markets buying and selling bonds from their customers, trading volumes in larger sizes have contracted. For example, only 13% of the trades that occurred for the 10 largest bonds in the index were $5 million or greater over recent periods. To put that in perspective, $5 million represents a 0.50% position for a $1 billion portfolio.

Exhibit 6: Investment Grade Debt Outstanding

Exhibit 7: Corporate Dealer Inventories

Exhibit 8: Percent of Corporate Trades Based on Size

Conclusion

This analysis has focused on the corporate universe because it is the largest credit related sector. A similar evaluation of the ABS and CMBS sectors would show even less flexibility given the smaller size of these markets. The industry can sometimes assume that larger managers provide superior returns given their size and market influence. However, this analysis demonstrates that size can actually limit the ability to implement relative value views across investment grade sectors or individual credits. Scale and trading limitations can result in portfolios with heavy allocations to Treasury and Agency related securities that are not desirable for income oriented insurance investors.

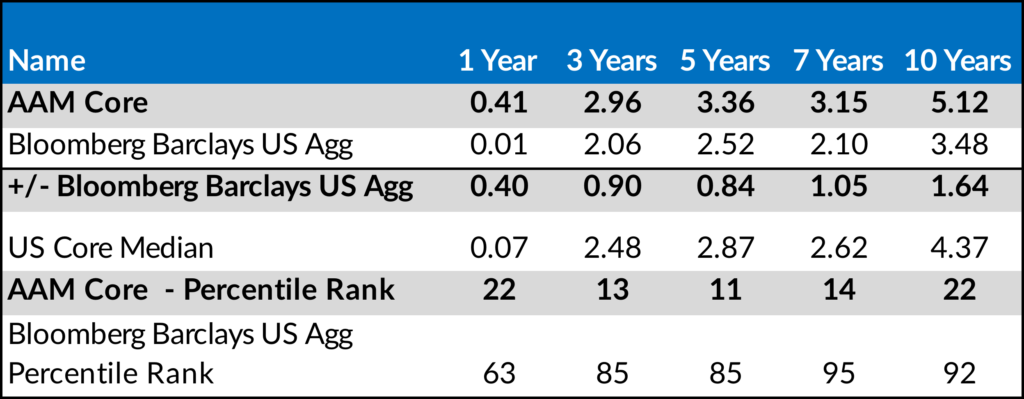

With this analysis, we have shown the connection between the size of a manager’s assets and their portfolio characteristics, which ultimately is reflected in their investment performance. Managers need scale and resources to successfully navigate the market, but being too large can limit execution of investment ideas. At AAM, our philosophy is that insurance portfolios require a yield-oriented approach within a risk-controlled framework. Our research capabilities and size allow the advantage of gaining meaningful allocations to the credit markets and effectively implementing trade ideas within portfolios. That combination has resulted in a track record of consistently competitive total returns.

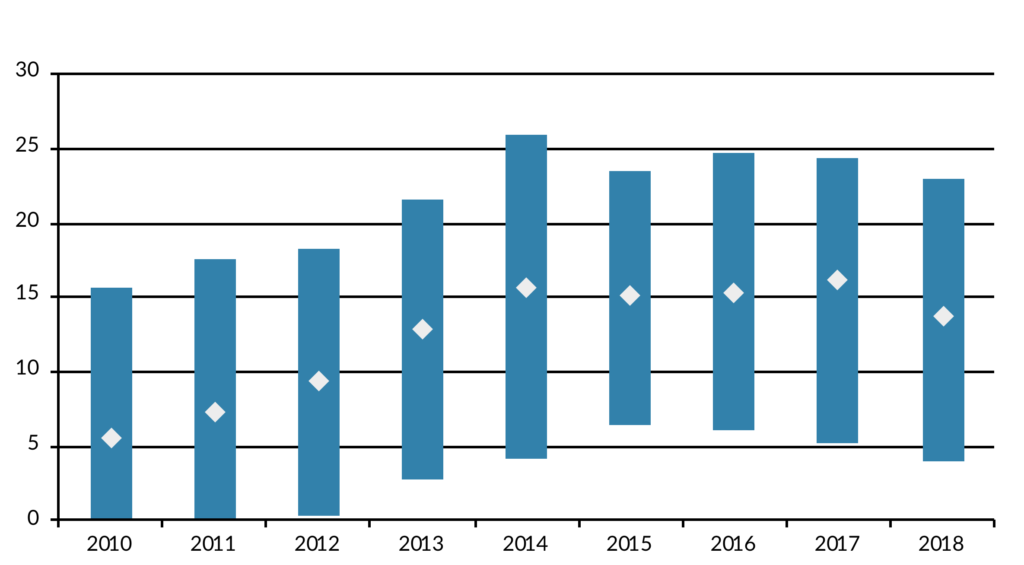

Exhibit 9: Annualized Returns

Exhibit 10: US Core Fixed Income Distribution of Returns