We believe investors should be aware of distressed exchanges given the increased number of fallen angels in the energy space and the negative influence that this liability management tool is having on bond prices and the high yield sector. In the following pages, we detail how an exchange typically takes place and why they are becoming more prevalent. We also provide a list of items that investors must consider when evaluating an exchange offer, review how the exchanges are influencing the high yield market, and review past exchanges. Unfortunately, there is no template for investors to use when deciding to exchange or not. Each exchange is unique, and a careful evaluation of many factors is necessary. This opinion is supported by the ultimate success of an exchange, which is slightly greater than 50/50 according to a New York University study1.

Distressed Debt Exchange Description

In a distressed debt exchange (DDE), a company proposes that existing debt holders take a haircut on their principal amount in exchange for moving up in payment priority in the form of secured debt. Generally, a distressed exchange is proposed by a company to avoid a bankruptcy, improve liquidity, reduce debt, manage its maturity dates (by exchanging debt securities that are coming due for debt securities with an extended maturity) and to reduce or eliminate onerous covenants.

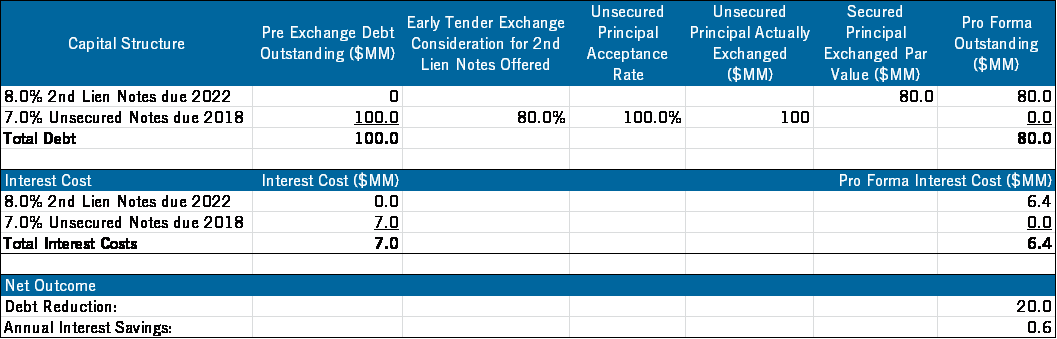

For example, XYZ Company has $100 million principal of 7.0% senior unsecured bonds due June 30, 2018. Due to market conditions, these distressed bonds are trading for $30, yielding 66% with a par value of $100. The company has little liquidity and external capital options are limited, so refinancing or repaying this upcoming maturity is doubtful. In order to avoid a costly bankruptcy, XYZ may offer to its bond holders the chance to exchange 100% of its 7.0% senior unsecured bonds maturing in 2018 for 80% of the original principal for new, 8% secured second lien debt maturing June 30, 2022. The new second lien debt will be issued at $50; yielding 25% based on peer trading levels and have a par value of $100. If all $100 million of principal is exchanged, the issuer will have eliminated the need to refinance in the near term (from 2018 to 2022), delayed a bankruptcy, reduced debt by $20 million (from $100 million to $80 million, also known as a Cancellation of Debt), and reduced annual interest expense by $0.6 million ($100 million x 7% – $80 million x 8%). Investors will forgo $20 million of principal, but will move to a secured position in the capital structure and see the price of its holding increase to $50 from $30. A secured position offers higher recovery values relative to an unsecured position if the company were to ultimately file for bankruptcy (See Exhibit 1).

The rating agencies play a role in DDEs as well. Based on their respective methodologies, if the exchange is viewed as effectively allowing the issuer to avoid bankruptcy or payment default, the rating agencies will take action to reflect the loss expected to be incurred by participating debt holders (e.g., Caa3, Ca, or C, using Moody’s scale). Otherwise, the agency will view it to be an opportunistic refinancing. Moody’s explains that often, the rating of the issuer is the determining factor of whether or not it is opportunistic. Debt exchanges from issuers rated B1 and higher are typically deemed as opportunistic refinancings vs. those rated Caa1 being viewed as distressed exchanges. This likely causes companies to pull forward the timing of the DDE, so the downgrade is less onerous.

Why are They Being Discussed Now?

DDEs are not new and have been used for decades. They have become more common in the last year following the surge in distressed energy companies. In fact, we are aware of at least a dozen energy companies that have employed this tactic since the beginning of 2015. Upon the completion of a DDE, the issuer will likely have reduced total debt and interest expense without using cash, thereby improving its credit profile modestly.

Reduced cash flows combined with inflated capital structures have contributed to an increase in liability management as a tool to delay or prevent a costly Chapter 11 default. In the Energy sector, lower commodity prices reduce companies’ borrowing bases, since banks use frequently updated asset values based on discounted cash flow analysis to determine borrowing-base availability. These updates, which generally occur every six months, are known as redeterminations. Exploration and Production (E&P) companies with unhedged production volumes leave themselves entirely exposed to low commodity prices, and risk significant borrowing-base reductions when the redetermination takes place. Banks generally give E&P companies some time to improve their liquidity, rather than take over the E&P assets themselves, but will take action if necessary.

Additionally, there are tax reasons for the increased use of this tool. Historically, if companies repurchased bonds at a discount, the difference between the par amount and the purchase price was a gain and taxed accordingly, significantly offsetting the benefits of the exchange. However, this changed in 2009 when the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act allowed deferral of most cancellation of debt (COD) income for five years and then allowed amortization of that COD over a five year period. Presently, section 108(a) of the Tax Code provides that in insolvency and bankruptcy the COD income is permanently excluded from taxation.

Evaluating a DDE Offer

When faced with a DDE offer, an investor must first determine the probability of default. Analyzing the issuer’s existing liquidity and the amount of time that the company can operate in the existing stressed environment should provide direction on whether or not a default is likely in the near term. If the investor is confident that a bankruptcy is unlikely and the issuer is simply attempting to take advantage of market conditions to reduce leverage via an exchange, then declining the exchange is the best course of action.

If a bankruptcy is more likely, investors should closely analyze and stress the company’s cash flows and multiples to determine a reasonable amount of debt that the company could support and receive court approval to emerge from Chapter 11. If the restructured company will only be able to support the amount of senior secured debt being offered as part of the exchange, then accepting an exchange offer should be strongly considered.

DDEs are usually voluntary and some holders of the debt may not exchange, which presents a holdout issue that investors must consider when deciding whether or not to accept the exchange offer. Importantly, debt exchange offers may be conditioned on the tender of a high percentage (e.g., 90% or more) of the debt sought in the offer. Such a minimum condition can provide comfort to holders who may otherwise be wary of exchanging debt securities at a discount if other holders who do not participate will reap the economic benefits of the exchange (i.e., the borrower’s improved balance sheet and ability to pay debts) without the cost. A minimum condition provides assurance that there will be, at most, a limited number of such free riders. Additionally, debt exchange offers can be structured to include various incentives such as secured debt and early tender premiums to holders to participate. Moreover, debt exchange offers can be combined with consent solicitations that propose, through an indenture amendment, to strip covenants and other protections from the debt sought in the exchange offer.

Another item to evaluate when considering an exchange is the influence of credit default swaps (CDS) owners on the issuer. Holdouts and the acceptance rate of the exchange will certainly be affected by those investors who own CDS. Bondholders that buy protection under CDS will be incentivized to force the issuer into bankruptcy in order to collect under their CDS contracts and therefore will likely not participate in efforts by the issuer to improve liquidity, extend maturities or reduce debt. The problem is increased if an issuer requires a high acceptance rate in order to make the debt exchange offer economically viable.

A final consideration in the exchange decision is estimating what liquidity there will be for the non-exchanged unsecured bonds. A significantly reduced total issue size will reduce liquidity of that issue, negatively affecting prices and likely incentivize holders to exchange. However, this concern is somewhat mitigated for holders of debt maturing prior to the secured notes offered as part of the exchange. The logic is that the improved credit profile of the issuer subsequent to the exchange could actually improve the likelihood that the original debt will be repaid. It will obviously mature first and the total funds required to repay or refinance the original debt that remains outstanding will be reduced significantly due to the exchange.

Influence on Today’s Market

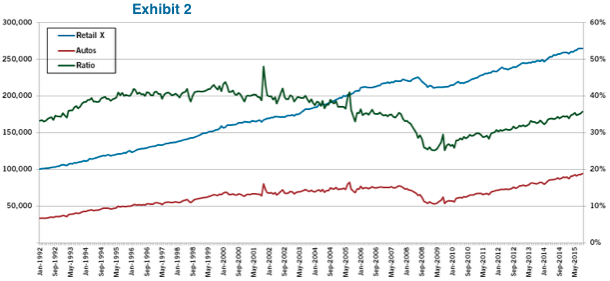

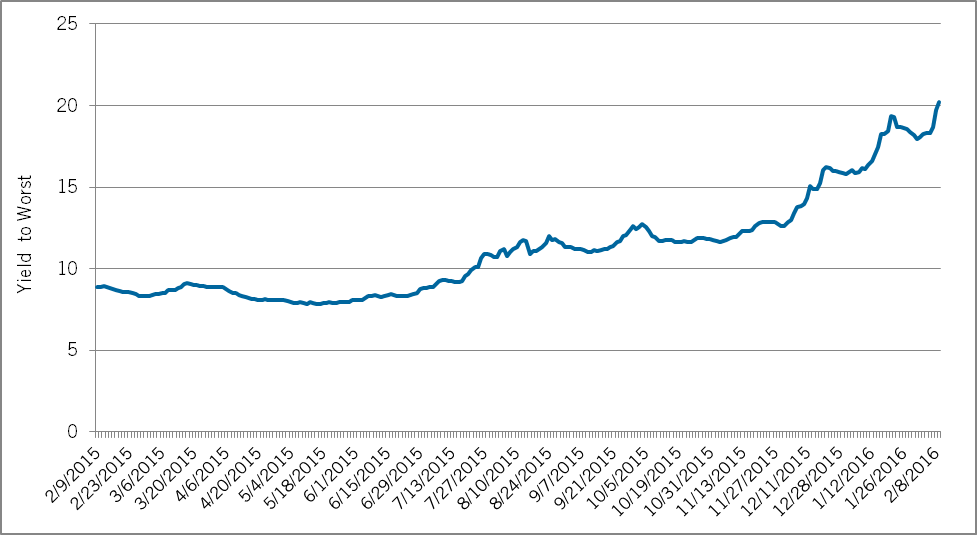

We believe the threat of more DDEs with potentially new senior secured debt has contributed to rapidly declining prices in the high yield energy market (Exhibit 2) for two reasons. The first result of this potential threat is an increase in the number of sellers of any issuer that has capacity to take on senior secured debt, regardless of whether or not there is an impending need for liquidity or solvency issue. The second result is that there are few investors willing to buy unsecured debt given the lack of confidence in the future capital structure of the investment. We believe this environment will persist until unsecured investors involved in exchanges demand more favorable terms, issuers provide assurances that there is no need for an exchange in the foreseeable future, and/or macroeconomic conditions improve.

Exhibit 2: High Yield Energy Yield to Worst

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch High Yield Energy Index (HOEN)

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch High Yield Energy Index (HOEN)

Evaluation of DDEs

We believe that the success of a distressed exchange should be viewed from the perspectives of the original investor, the distressed investor and the issuer. It is too early to determine the outcome of the exchanges from the investors’ perspectives in the recent energy related transactions. However, it appears as though those companies have merely delayed the inevitable default at this point, which probably favors those investors that accepted the exchange offer.

If a DDE is eventually followed by a bankruptcy, the restructuring efforts could be characterized as unsuccessful. However, we believe that the exchanges have achieved several of the companies’ goals. The exchanges have in fact partially extended near term maturities, reduced total debt and interest expense, allowing the companies to postpone a costly default in hopes of a recovery in the operating environment.

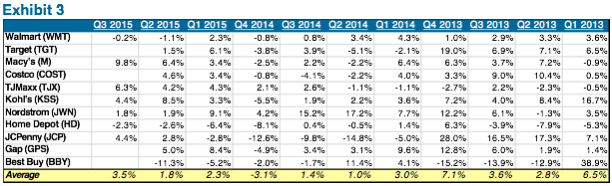

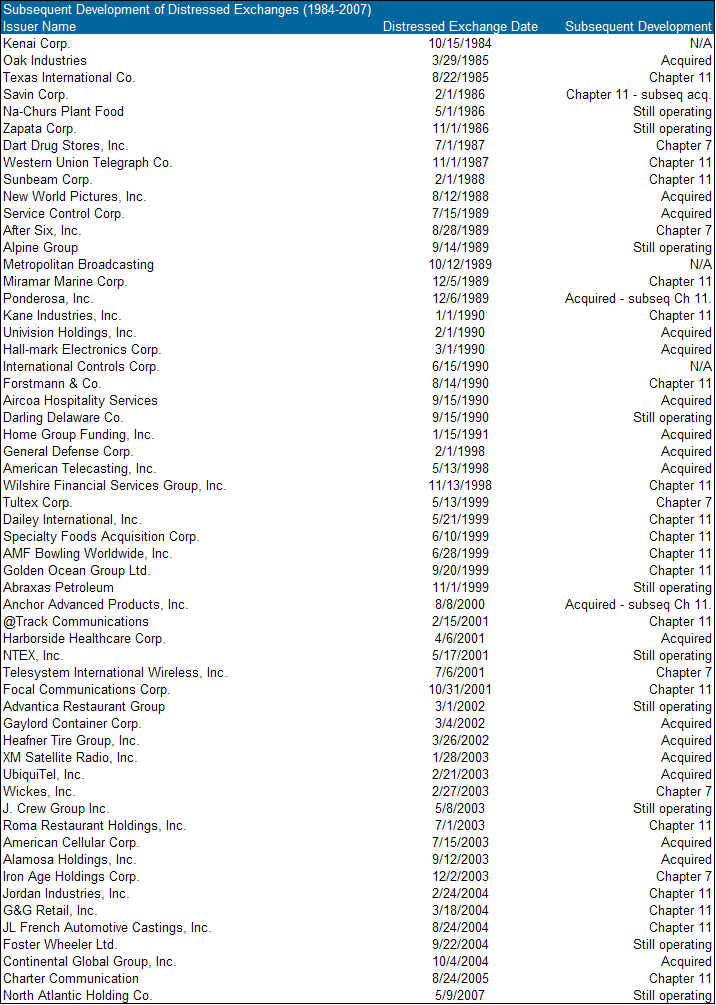

Studies of the outcomes of previous exchanges have to be viewed cautiously because few such transactions have taken place. Out of 57 DDEs to take place from 1984- 2008, 26 (46%) were followed by a bankruptcy filing (20 Chapter 11 reorganizations and six Chapter 7 liquidations), seventeen (30%) firms were eventually acquired, while 11 (24%) were still operating in 2009 (Exhibit 3). Additionally, the recovery rate of the exchanged debt that eventually defaulted was 52%, whereas, the recovery rate for the 875 non-DDE defaults in that same period was 42%.

Exhibit 3: Subsequent Development of Distressed Exchanges (1984 – 2007)

Source: The Reemergence of Distressed Exchanges in Corporate Restructurings (2009), AAM

Source: The Reemergence of Distressed Exchanges in Corporate Restructurings (2009), AAM

Conclusion

Market participants believe debt exchanges are going to accelerate in the upcoming year as distressed energy companies attempt to reduce debt, improve liquidity, and delay a costly bankruptcy. Other companies may seek to take advantage of the weak environment and offer an exchange despite not having a liquidity or solvency issue in the near term. We have outlined several critical factors to analyze when deciding to accept an exchange offer or decline. We believe this knowledge prepares us to make disciplined investment decisions in the event we are faced with deciding against an exchange offer or accepting less than the original promised principal.

Written by:

Patrick McGeever

Senior Analyst Corporate Credit

1 Edward I. Altman and Brenda Karlin, “The Reemergence of Distressed Exchanges in Corporate Restructurings,” (March 2009) accessed February 11, 2016, https://people.stern.nyu.edu/ealtman/Reemergence%20of%20Distressed%20Exchanges.pdf

2 Edward I. Altman and Brenda Karlin, “The Reemergence of Distressed Exchanges in Corporate Restructurings,” (March 2009)

Lenny Aizenman et al., “Distressed Exchanges: Implications for Probability of Default Ratings, Corporate Family Ratings and Debt Instrument Ratings,” Moody’s Global Corporate Finance, (March 2009)

3 Ze’-ev D. Eiger et al., Liability Management Handbook 2015 Update, International Financial Law Review, 82, accessed February 11, 2016, https://media.mofo.com/files/Uploads/Images/MofoLiabMan.pdf

4 “Debt Exchange Offers in the Current Market,” The Bankruptcy Strategist, Law Journal Newsletters, Volume 26, Number 9 (July 2009)

5 “Debt Exchange Offers: Legal Strategies for Distressed Issuers – Navigating Complex Securities Laws When Restructuring Convertible Debt Securities,” 7, (April 15, 2010). Accessed February 11, 2016, https://media.straffordpub.com/products/debt-exchange-offers-legal-strategies-for-distressed-issuers-2010-04-15/presentation.pdf

6 Edward I. Altman and Brenda Karlin, “The Reemergence of Distressed Exchanges in Corporate Restructurings,” (March 2009)

For more information, contact:

Colin T. Dowdall, CFA

Director of Marketing and Business Development

colin.dowdall@aamcompany.com

John Olvany

Vice President of Business Development

john.olvany@aamcompany.com

Neelm Hameer

Vice President of Business Development

neelm.hameer@aamcompany.com

Disclaimer: Asset Allocation & Management Company, LLC (AAM) is an investment adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission, specializing in fixed-income asset management services for insurance companies. This information was developed using publicly available information, internally developed data and outside sources believed to be reliable. While all reasonable care has been taken to ensure that the facts stated and the opinions given are accurate, complete and reasonable, liability is expressly disclaimed by AAM and any affiliates (collectively known as “AAM”), and their representative officers and employees. This report has been prepared for informational purposes only and does not purport to represent a complete analysis of any security, company or industry discussed. Any opinions and/or recommendations expressed are subject to change without notice and should be considered only as part of a diversified portfolio. A complete list of investment recommendations made during the past year is available upon request. Past performance is not an indication of future returns.

This information is distributed to recipients including AAM, any of which may have acted on the basis of the information, or may have an ownership interest in securities to which the information relates. It may also be distributed to clients of AAM, as well as to other recipients with whom no such client relationship exists. Providing this information does not, in and of itself, constitute a recommendation by AAM, nor does it imply that the purchase or sale of any security is suitable for the recipient. Investing in the bond market is subject to certain risks including market, interest-rate, issuer, credit, inflation, liquidity, valuation, volatility, prepayment and extension. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission.